🦇 How Bats Help Keep Our River Clean 🦇

When you think about things that improve water quality, you probably picture salmon, beavers, or volunteers planting trees. Interestingly, even though they are not considered aquatic animals, bats are quietly protect our waterways every evening — and most people don’t even know it.

A single bat eats up to 1,000 insects per hour — including mosquitoes and agricultural pests that lead to pesticide use.

By naturally reducing pest pressure, bats help farms and homeowners rely less on chemical sprays — which means cleaner water flowing into the Clackamas River.

Some bat species even pollinate and spread seeds, helping forests rebound after wildfire and disturbance.

Healthy bat populations = healthier ecosystems for salmon, wildlife, and people.

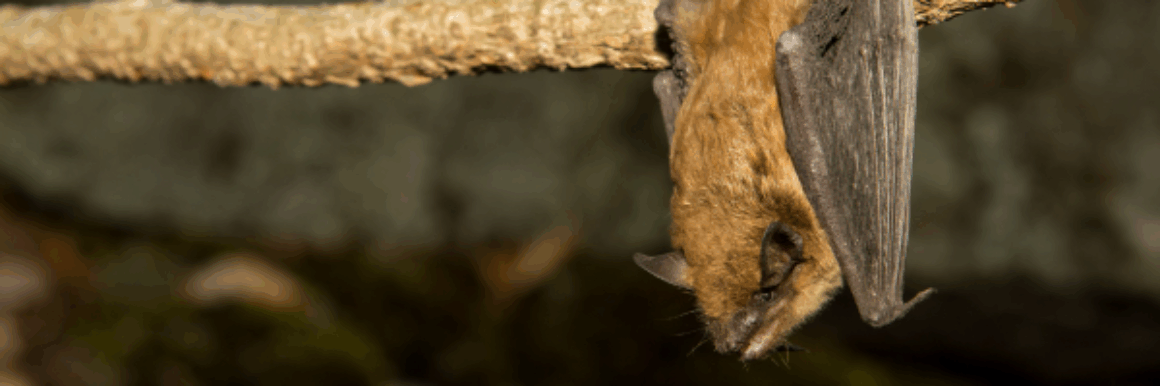

About Oregon’s Bats

Oregon has 15 species of native bats (links take you to Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s website for a description of each):

Threats Facing Oregon’s Bats

-

Loss of forests and natural roosting sites

-

Pesticide exposure

-

White-nose Syndrome (see more below!!)

The good news? You can take direct action to protect bats and the Clackamas River.

Protect bats — Choose One Action Today

1. Take the Clackamas River Basin Council’s Pesticide Pledge

Small changes in your yard protect both bats and salmon habitats.

2. Volunteer for Habitat Restoration

Join us for native plantings, invasive weed pulls, and riverside events that protect bat habitat.

3. Join Our Email List

Stay updated on wildlife stories and restoration projects, tips on how to protect wildlife, and local stewardship events.

How to Help Protect Bats from White-Nose Syndrome in Oregon

White-nose Syndrome (WNS) is one of the most serious threats to bats in Oregon and across North America. It’s caused by a cold-loving fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) that grows on hibernating bats and disrupts their sleep cycles — often causing them to burn through fat reserves and die before spring.

While WNS spreads primarily bat-to-bat, humans can unintentionally carry fungal spores on shoes and gear, so public action does matter.

1. Stay Out of Bat Roosts and Caves (Unless Permitted)

Avoid entering caves, mines, or tunnels where bats may hibernate. Even if the fungus isn’t visible, it may be present.

2. Decontaminate Boots & Gear

If you have been in caves or rocky areas, clean your shoes, clothing, and equipment using official decontamination guidelines from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Better yet, never wear the same clothing in different caves.

👉 Even hiking boots can spread spores from one habitat to another.

3. Never Disturb Roosting or Hibernating Bats

Waking up a bat in winter can be lethal, even without WNS — they burn critical energy every time they flee or relocate.

4. Report Sick or Dead Bats

If you find a group of sick, grounded, or dead bats — do not touch them — but report it to:

- ODFW Wildlife Health Lab → 1-866-968-2600 or wildlife.health@odfw.oregon.gov

5. Support Natural Habitat Instead of Artificial Roosts in Winter

Bat boxes are great for summer roosting, but should not be assumed safe for winter hibernation unless designed and monitored specifically for that use — improper boxes can expose bats to temperature swings.

6. Reduce Pesticide Use & Protect Insect Habitat

A well-fed bat is a resilient bat. Less pesticide = more moths & beetles for bats to eat = stronger immune systems heading into winter.

7. Educate Others (Especially Outdoor Rec Users)

White-Nose Syndrome spreads silently. Most people don’t realize that their boots or climbing gear could be a vector.